I continued west towards the setting sun, now almost invisible behind the snow-encrusted ramparts of the distant ranges.

West of Riverton, State Highway 99 undulated through a bucolic landscape of rolling, lime green hills, their sensual curves highlighted by the lowering afternoon sun. Sheep dotted the paddocks and shelterbelts, stark against the blue of the sky, broke up the skyline. The road crossed the estuary of the Jacobs River at Riverton and skirted the southern edge of the Longwood Forest.

The Longwood Ranges were a major gold-mining center in the latter half of the nineteenth century. After gold was discovered at Round Hill, one of the peaks in the range, in 1870, European miners began working claims in the area. Plagued by a lack of water for sluicing the gold-bearing gravel from the hillsides, the mining operation was slowly abandoned until Chinese miners arrived in 1880. The industrious Chinese patiently began re-working the unoccupied claims, winning the gold that the earlier miners had missed.

By 1882, the were five hundred Chinese living and working at Round Hill. The encampment was informally renamed Canton and was the largest Chinese community in New Zealand at the time. It was the southernmost settlement of Chinese in the world. Mining continued in the Longwood ranges until the 1950s when the gold finally played out.

At Orepuki I met the coast. The long sweep of Te Waewae Bay stretched away towards the distant peaks of Fiordland. The lower limb of the sun was touching the ranges and casting shadows of their tall, ragged silhouettes out into the hazy air. I turned off the highway at Gemstone Beach and drove down a short, sandy track through dunes covered in marram grass to a rough parking place. A sign on a open gateway read: No Parking, Mental Health Patient Lives Here. I presumed it was some crude reference to the reaction the unseen resident would have if someone blocked his exit.

The waters of Te Waewae Bay lay blue and calm below the dunes. Long easy, lines of waves rolled in towards the beach and tumbled lazily onto the sand. The southern end of the beach was framed by crumbling cliffs of orange clay interspersed with black layers of peat. A lurid sign, featuring a hapless stick figure being crushed by angular blocks of falling from an overhang, warned people not to walk under the cliffs. Beyond it, the beach curved round to a low, grassy headland with a collection of shining cribs nestled in its lee.

Beyond Tūātapere, the landscape grew cold and wild. Heavy stands of native forest crowded the road. A white rime of frost clung to the hollows.

I continued west towards the setting sun, now almost invisible behind the snow-encrusted ramparts of the distant ranges. The road skirted the edge of the land, which fell abruptly to the curving beach in a series of lustrous green ridges, shimmering in the last burnished light of the day. Smoke curled upwards from farmhouse chimneys and herds of cows made their way languorously back to their paddocks after the afternoon milking.

Tūātapere lay smoundering in the shadow of the ranges. The sluggish Waiau River, framed with dense groves of flax, bordered the southern edge of the town. Pyramids of newly-felled logs stood in timber-yards on the main road. A forestry town, Tūātapere has the look and feeling of an outpost; a last bulwark of civilization on the edge of Fiordland.

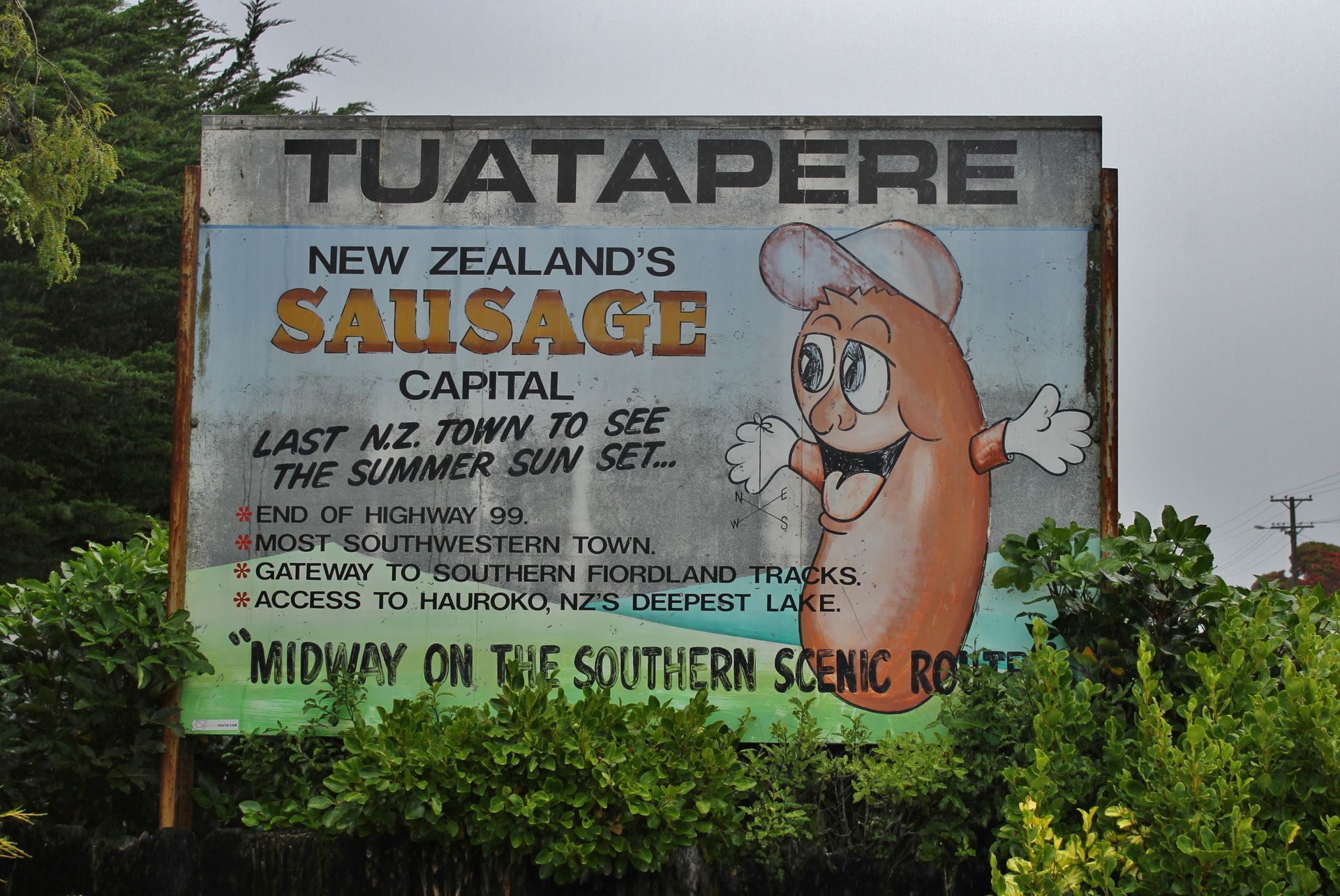

Surprisingly, Tūātapere bills itself as “The Sausage Capital of Southland”, an odd claim to fame given its isolation. Although I didn’t feel like sampling whatever sausagey fare the town might offer, I was happy to see that Spark, in their infinite wisdom, had provided a free wifi connection next to the Four Square Supermarket. Feeling that it would be my last chance to avail myself of complementary data, I uploaded my Snapchat story, posted an Instagram photo of Gemstone Beach, and continued west into the gathering dusk.

Beyond Tūātapere, the landscape grew cold and wild. Heavy stands of native forest crowded the road. A white rime of frost clung to the hollows. The darkening ocean lay out beyond the edge of scrubby fields of bracken fern. The tarmac road gave way to gravel, potholed and riven with corrugations which made the suspension judder and shake. Shaggy Hereford-Angus beef cattle stared balefully from behind fences of barbed wire.

On a damp, slippery cutting, half clay and half gravel, I encountered a logging truck and trailer, fully-laden with logs, bogged in the road. The skidding wheels had carved up the road’s surface. A pair of unhappy truckies, both wearing shorts and high-vis vests, stood smoking beside the cab. The trailer was half off the road, and canted sideways into a ditch.

“Got any beers in the back?” asked one of the men hopefully as I pulled up beside them. I turned the engine off and replied that I didn’t.

“I’ve got a two tonne towing strop,” I said, facetiously, looking at the bogged rig. My tiny Subaru, as powerful as it was, would have no chance of helping. But it lightened their mood and, reaching into the glove compartment, I extracted a bag of lollies.

“Haven’t got any beer,” I said. “Have a licorice allsort though.”

They took two each and I asked what had happened.

“Fuckin’ thing lost traction halfway up,” said the younger of the two. “And when I tried to back back down to firmer ground the cunt slid off the fuckin’ road.”

His older companion blew a cloud of tobacco smoke into the frigid air and nodded. “Not the first time it’s happened just here,” he said, as if to allay the younger driver’s obvious embarrassment. His rig, another truck and trailer, fully loaded with logs, stood at the bottom of the cutting.

We introduced each other and I offered to take them back out to where they could get cell phone coverage to call for help.

“Nah mate,” said James, the younger driver. “We’ve radioed out for another truck to come over from town and pull it out. Just gotta wait for it to get here.”

“Where the fuck you going at this time of day anyway?” asked Dave, the other man.

I explained that I wanted to drive as far west as it was possible to go and that I planned to sleep in the back of my truck. Both men looked at me as if I was nuts and, indeed, it did sound preposterous, stupid even.

Dave gave me some vague directions to follow, told me not to go through a certain gate which might get locked behind me, and we discussed whether or not it was even possible for me to get past James’ rig. I left them standing there in the twilight, rolling cigarettes and swearing, and squeezed past the mud-splattered wheels of the truck, my own little rig half off the road in the long grass. At the bottom of the hill I reached the end of the public road at the Hump Ridge Track carpark.

As I drove deeper into the forest it became progressively darker and colder. In places the road was flooded, the surface of the water frozen into a thick layer of ice.

The Hump Ridge Track was first cut in the late 1890s to provide access for the logging of the vast tracts of native forest which grew along the southern coast of Fiordland. The track was a herculean effort of ingenuity and hard work. Leaving aside the violence and vagaries of the weather in this part of the South Island, where rainfall is measured in metres, the landscape posed some huge challenges for the builders of the track. Massive rivers which flooded often had to be bridged. Deep, sheer-sided ravines needed to be spanned with timber viaducts. The freezing winters, the frequent rain, and the cold winds which blew almost constantly, must have made living and working in this extremity of the world an exercise in pure masochism.

But the payoffs were immense. The nascent country needed building material, and the native forest species, especially kahikatea, rimu, and matai, yielded exceptionally strong and durable timber. A timber mill to process the felled trees was established in 1920 at Port Craig, forty-five kilometres along the coast from where I was now. At the time, it was the largest sawmill in New Zealand and employed two hundred workers. The ravines were spanned by some of the biggest viaducts ever built in New Zealand. The largest of these, the Percy Burn Viaduct, is 125 metres long and 36 metres high.

The viaduct is still standing today and is the one of the biggest wooden viaducts in the Southern Hemisphere. It was fully restored in the 1990s when the then Labour government established the Hump Ridge Walking Track. Although at the time the walking track, which cost over three million dollars to build, was criticised as a vanity project for the Prime Minister, Helen Clark, it has since become a popular and well-used walk. Tourism has, in fact, revitalised the Tuatapere area and people from all over the world come to do the three-day Hump Ridge walk.

Beside the car park, a battered pipe and netting gate blocked the road. A hand-painted sign, similar to the one I’d seen at Gemstone Beach, warning of the mental state of the owner, announced that there was a charge of five dollars to use the road beyond this point. A box made from boiler plate with a slot cut into it was, presumably, where you deposited the cash if you were dumb enough to be fooled by this.

As I was reading the sign, a battered red car, its headlights gleaming dully in the damp air, slithered down the greasy track and pulled up on the opposite side of the gate. I dutifully swung the gate open and waved at the two grim-faced, bearded men inside. They drove through without a glance or a thank you, the miserable fuckers. Perhaps they were logging contractors, following the trucks out after a day of felling trees. Maybe they were hikers, or dope growers. Hell, they could have been murderers heading home after disposing of a body, a job which, incidentally, would be relatively easy out here in the empty, forbidding wilderness which lay ahead of me.

In any case, I thought, they weren’t Irish tree fellers…because there was only two of them. Giggling at my own wit, I drove through the gate (without paying), closed it, and headed west into the wilds of Fiordland.

Fiordland National Park, the eastern edge of which I was now, somewhat tentatively, driving into, occupies the entire south-west corner of the South Island: an area of around thirteen thousand square kilometres. That’s roughly the same size as the American state of Connecticut.

Riven by fjords, the drowned valleys of former glaciers, and clad with almost impenetrable rainforest, Fiordland (the name is derived from a variant spelling of fjord) is a wilderness, virtually devoid of human habitation. With the exception of Milford Sound, the Milford Track, and a few other tourist hotspots, Fiordland is empty. Access is limited to helicopters and, in the case of the rumpled outer edge of the island, where the full force of the Southern Ocean collides with the land, sturdy and well-equipped boats.

“when vegetation rioted upon the earth and the big trees were kings.”

Trawlers and lobster boats are, essentially, the only craft which ever visit the isolated sounds on the south-west tip of the island. The sounds have evocative names that conjure images of wild seas, wild country and tough explorers. Many of the landforms – Dusky Sound, Breaksea Sound, Wet Jacket Arm, Acheron Passage – on the outer edge of Fiordland were named by Captain James Cook as he sailed The Endeavour

slowly southabout the island. My favourite of the names he conferred is Doubtful Sound, which got its title because Cook recorded in his ship’s log that it was “doubtless, a sound.”

Beyond the gateway, the road deteriorated into a rutted, muddy track. The passage of countless logging trucks had broken through the gravel surface and created long stretches of mud. Bracken fern grew right to the edges of the road, and the snapped, truncated stumps of trees leaned over above.

But I’m no stranger to rough, four-wheel-drive tracks and I had absolute faith in my little Forester to make it through. Besides, I thought, the murderers/loggers in the red car had just driven along here, so it couldn’t be too bad. Nevertheless, I pulled the transfer lever upwards into the Lo-range position.

At a fork in the road I chose the left-hand option. The right-hand track led through an open gate with a heavy chain and padlock on it. This, I presumed, was the gate that Dave had warned me not to go through. I descended an escarpment clad in a plantation of eucalyptus, their stringy bark hanging in long tendrils from their tall, slim trunks. Their presence here, in this cold, wet place seemed incongruous, vastly at odds with the hot, dusty, brightly-lit Outback country of Australia, their natural habitat.

As I drove deeper into the forest it became progressively darker and colder. In places the road was flooded, the surface of the water frozen into a thick layer of ice. Along both sides of the road, the bracken, grass and shrubbery was rimed with a heavy white coating of frost.

My headlights cast a feeble glow into the frigid twilight, halfway between daylight and darkness, ahead of me. To keep my spirits up, I selected a Spotify playlist of electronic dance music on my phone. As the kick-drum thud of an Armin van Buuren song boomed from the speakers I crossed a black river, hemmed by dark, overhanging trees, on a bridge of hewn logs. On the far side, I crested a ridge and saw, for the first time, the vastness of the landscape into which I was heading.

In Heart of Darkness

, his novella set in the jungles of the Congo Basin, Joseph Conrad describes a time “when vegetation rioted upon the earth and the big trees were kings.” In Conrad’s day, the late nineteenth century, the big trees would still have been here. Now, they were all gone. The sawmillers of Port Craig had taken care of that. But now, after a hundred years of being left alone, vegetation was once again rioting upon the Earth. Before me lay a rumpled expanse of regrowth forest, stretching away towards the distant Hauroko Range, now just a vague snowy skyline on the western horizon.

I had expected to be able to see the coastline bending away to the south-west. But the ocean was gone, replaced by a seascape of forest and the dark heave of the Hump Ridge. I stopped the truck, turned off the music, the engine and the lights, and stepped out into the motionless evening. In the silence I could hear the whisper of an unseen river in its bed of stones. Somewhere, a stag roared, guttural and blood-curdling, like the sound a dragon would make. Behind me, a big full moon, the colour of chardonnay, was rising through the trees.

I thought of the lines from the poem Dominion

by the New Zealand poet A.R.D. Fairburn:

and the night sky, closing over, covers like a hand

the barbaric yawn of a young and wrinkled land

I stood there in that vast space, feeling very small and alone. I was as though I was about to step off the edge of the Earth. No one knew where I was. Dave and James probably wouldn’t remember me passing by. The coves in the red car had paid me no mind. I hadn’t even put five bucks in the boilerplate box. If something went wrong – a flat battery, getting stuck – it would mean a long walk and an expensive rescue. The forest suddenly seemed vaguely threatening in its cold silence: aloof, implacable, utterly impersonal.

It was time to let discretion be the better part of valour. I had accomplished my objective, which was to drive as far west as it is possible to go in the South Island. To go on, though mildly heroic, was, at best, a bit pointless. At worst, it was just plain stupid. I returned to the warmth of my truck, with its thudding music and its heater. Turning round on the slippery ground I was at pains not to go too close to the edge of the road. To get bogged now would’ve sucked big time.

Driving back out of the forest, the moon played games with me, sometimes appearing to the right of the road, sometimes winking through the treetops on the left. In the darkness, with the road unfolding ahead of me in the headlight, my spatial awareness became unsteady. It was only the rainforest moon, hanging like a beacon in the eastern sky that kept me on track.

I re-crossed the log bridge, skirted the frozen pool, passed by the now locked forestry gate and descended to the five dollar road gate. No one was around. There were no lights on in the nearby farmhouse. I closed the gate like a sneak thief and drove away. Up the hill, the logging trucks were gone. All that remained were the gouges in the road where James’ truck had been bogged.

Excerpt from The Greenstone Water