Out here nothing changes,

not in a hurry anyway.

You feel the endlessness,

running on the light of day…

– Goanna, Solid Rock

Before the Dreamtime there was nothing. The Earth was flat and lifeless; no stars glittered in the sky. The universe was dark and silent. The Ancestors lay sleeping, deep in the ground where they had passed the ages. But the Ancestors were restless; their long sleep was nearing its end. On the first morning of the world they awoke, flexed their ancient limbs and began calling the world into existence.

Emerging from the ground they created the stars and the moon. They created the animals – the frilled lizards, the snakes and the kangaroos – and the rains. They brought forth all the rainbow-hued birds and created trees in which the could live. They made the people, the laws and language and dance. They carved the rivers, filled the seas and built the mountain ranges. And as they brought the world to life, the Ancestors walked the land, naming the places and singing songs of the creation.

The story of Lungkata was also a blueprint, a route map, a recipe book and a parable.

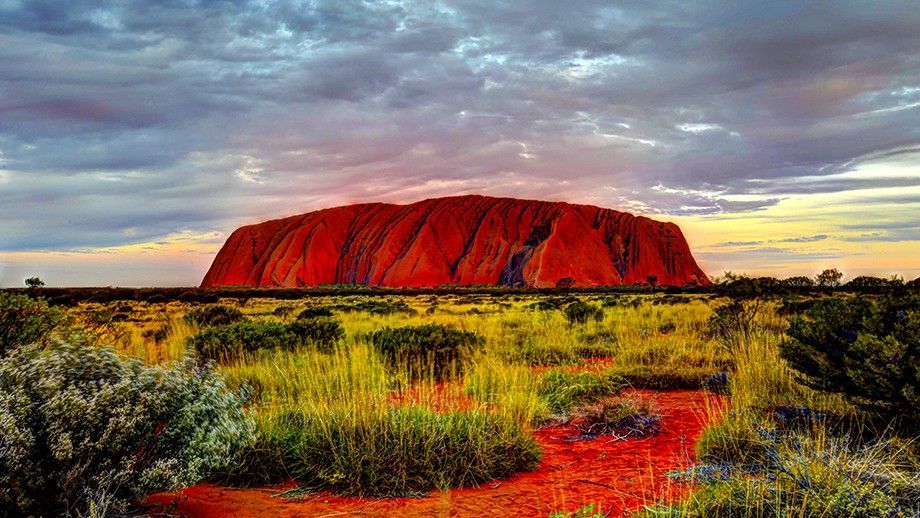

At Uluru I came face to face with these Dreamtime stories, etched into the flanks of the great red stone white men named Ayers Rock. On the 1800 kilometre flight west from the rainforests of Far North Queensland, I had travelled back in time both literally (the Northern Territory is half an hour behind Eastern time) and figuratively, to the six hundred million year old Red Centre of Australia. The landscape which unfolded beneath the aircraft’s wing seemed so old it was almost worn out. Its features – dry creek beds, bony ridges, rumpled sand dunes – looked like blood vessels and sinews in the back of an old man’s hand.

The aircraft’s final approach took us over Uluru at dusk. As the pilot executed a banking turn into Connelan Airport, I had a glimpse of the rock standing pink and mauve amid a sea of sunset orange. The surrounding landscape was covered with desert vegetation: yellow spinifex grass, desert oaks, mulga trees and a profusion of desert flowers which had sprung to life after a recent rainstorm.

Archeological evidence suggests that Aboriginal people have lived around Uluru for at least 10,000 years. According to the tjukurpa (pronounced “chooka-pa”), or law, of the local Anangu people, Uluru was built by two boys who played in the mud after the rains which followed the creation. In Anangu legend the three central ancestral beings of the creation were the Mala (rufus hare wallabies), the Kuniya (woma pythons) and the Liru (poisonous snakes). The stories of each of these beings is engraved onto the surface of Uluru in the form of protruding rocks, snake-shaped cracks, ocular caves and dozens of vaguely human and animal profiles.

The following morning I went walking with Jacob Puntaru, an Anangu elder, and Kathy Tozer, a white Australian who has developed a close rapport with the Anangu people. Kathy interpreted my questions for Jacob and translated his replies. We followed a path through olive-green mulga trees to a clearing where we sat while Jacob lit a fire. His skin was as black as night; his face and hands had been deeply wrinkled by the bright Central Australian sun. As the astringent eucalypt smoke swirled around us, Jacob related the story of Lungkata, the blue-tongued lizard.

“Long ago,” he said, “Lungkata traveled up from his country to Uluru. He came across Panpanpalala, a bell-bird man, who had killed an emu and had set about cooking it. The bell-bird man was asleep so Lungkata stole the emu and took it to a hideout, way up there.”

Jacob paused and pointed to a small cave notched into the rock near the summit of Uluru.

Uluru.

“When the bell-bird man discovered his emu gone he went to ask Lungkata if he had seen it. Lungkata replied that he hadn’t. But Lungkata had broken a sacred law by stealing the emu and as punishment the bell-bird man set fire to the rock. Lungkata was burned and fell to his death.”

The sheer face beneath the cave was blackened as if a fire had, indeed, swept the rock. Jacob waved his hand towards the foot of Uluru.

“Over there you can still see pieces of the emu lying on the ground turned to stone,” he said. “And the tail of Lungkata is poking from the ground nearby.”

As I listened to the story I realized that what I was hearing wasn’t simply an entertaining tale. The story of Lungkata was also a blueprint, a route map, a recipe book and a parable. The information imbedded in this and every Aboriginal legend has been passed down through the generations. With each telling, more information would be added to the story. So a person traveling to Uluru would be able to go over this and other stories in his mind and divine the best route, where to find food and water, how to cook the food he found and how to behave when he reached his destination.

To the untutored European ear, Aboriginal stories seem nothing more than quaint works of native fiction. Yet the parable of Lungkata has a deep significance for modern visitors to Uluru. Before the advent of tourism, only initiated Anangu men were allowed to climb Uluru. But nowadays, with hundreds of people clambering up the steep path to the top of rock each day, accidents are bound to happen. When a person falls to their death, and the Anangu hear the helicopter rotors thrashing the hot air as the body is recovered, they see it as the legend of Lungkata coming true.

“This is not something I made up to entertain visitors,” Jacob Puntaru said. “These things really happened and you only have to look at the rock to see the proof.”

The sand underfoot was the colour of chili powder and every bit as hot.

Later, I set off to walk the nine-kilometre path around the base of Uluru. The rock rose from the desert in great billows like an enormous petrified wave. Its deep red colour was bought into sharp relief by the intense blue of the sky. Iron oxides ran in stripes through the stone which felt cold when I touched it, like the skin of a reptile.

It was easy to see how the Anangu could read stories into every crease and bulge of Uluru. Staring up at the rock from the sparse shade of a bloodwood tree I could see a dingo’s paw, a human face, the pock marks of spear-thrusts and a coiled snake.

The sand underfoot was the colour of chili powder and every bit as hot.

Occasionally, a breeze would come out of nowhere, blow for a few minutes, then fade to nothing.

These desert zephyrs, however fleeting, were a welcome relief from the heat and made me less envious of the tourists cruising by in air-conditioned buses.

The sand underfoot was the colour of chili powder and every bit as hot.

Occasionally, a breeze would come out of nowhere, blow for a few minutes, then fade to nothing.

These desert zephyrs, however fleeting, were a welcome relief from the heat and made me less envious of the tourists cruising by in air-conditioned buses.

It took three hours to circumnavigate Uluru. As I explored the rock’s recesses and gorges I began to sense the endlessness of time out here. The domes of nearby Kata Tjuta and the monolithic bulk of Uluru have seen the sun rise for 109 billion mornings. We humans, on the other hand, have existed for a mere eye-blink of time by comparison.

After a cold drink, I headed west in my rented 4WD. The sun dissolved the road into a shimmering mirage: the landscape swam and wobbled in the heat as if I was looking at it through a glass bottle. The sky was incandescent, the colour of burning magnesium. Ahead of me, the domes of Kata Tjuta rose from the desert like a cluster of bald heads.

To the Anangu people, Kata Tjuta (also known as the Olgas) is a deeply sacred place. For 10,000 years they have lived around these 36 strange red rocks – whose name means “many heads.”

The car park at Olga Gorge was empty. Leaving my vehicle parked in the meager shade of a mulga bush, I set off along a rocky path leading upwards between the highest domes. The air was blisteringly hot. Dunnie budgies (flies) swarmed around me. The domes were composed of orange pebbles cemented together with coarse red gravel the consistency of crumbled biscuit. Time, wind and water had sculpted their sheer sides with Mondrian-style stripes, grooves and fissures.

As I climbed higher the gorge narrowed, constricted between the sheer walls which seemed to lean inwards until the sky was reduced to a crack of cobalt blue overhead. A wooden observation platform stood amid stunted bushes at the head of the gorge. Had I been there at sunrise or sunset the view would have been stunning. But the afternoon air was suffocatingly hot – each breath felt like I was inhaling molten treacle – and the determined hordes of flies detracted from my enjoyment of the vista. After a short time I decided to retreat.

In the endless sea of scrubby desert surrounding Uluru, the Aboriginal people have found all they need to sustain their culture, the oldest on Earth.

As I walked back down the gorge, a squadron of tour buses materialized in the car park as if created out of the hot air. A crowd of sweating tourists began toiling towards me, swatting at the flies and stumbling over the rough ground in shoes more suited to a cocktail bar than an outback hillside. I saw an American woman wearing rubber kitchen gloves and a face mask and carrying a can of fly spray.

On the way back to Yulara (the village which provides amenities for Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park) an Aboriginal man flagged me down. His wife and two children sat in the shade of a battered Holden station-wagon playing cards.

“Buy us some beer would ya mate,” he asked through the open passenger side window. It is a request tourists often hear around Yulara. The Anangu elders have declared the area “dry” and the only way Aboriginal people can obtain alcohol is by getting tourists to buy it for them. I was tempted to oblige him – I was hankering after a cold beer myself – but out of respect for the local by-law I politely refused and gave him some cans of lemonade for his kids.

I rose at 4.00 am next morning to watch the sunrise light up Uluru as it has done for the last 109 billion mornings. Parked between two tour-buses I sat on the roof of the 4WD in the chilly darkness before dawn. The bulk of Uluru was nothing more than an area of blackness against the starry sky. But as the light grew stronger the rock began to glow, first a pale blue, then deep purple and finally, in the instant before sunrise, a rich ochreous red.

Within minutes, the tour-buses departed, conveying their passengers to buffet breakfasts in air-conditioned hotels. I was alone in the desert.I thought about the stories Jacob Puntaru had told me the previous day. In the endless sea of scrubby desert surrounding Uluru, the Aboriginal people have found all they need to sustain their culture, the oldest on Earth. They recognize the interconnectedness of all things, from grains of sand to the mightiest of mountains. While Europeans see the land as a resource to be exploited and changed to suit them, Aboriginals see themselves as keepers of the land and strive to keep it the way it is: part of the never-ending legend of the Dreamtime.