My great-grandfather, Charles Robert Blakiston, came to New Zealand in 1860, having first tried his luck in the Australian goldfields.

I come from Geraldine. Someone had to. My hometown, Geraldine, on New Zealand’s South Island, doesn’t have any notable citizens. We can’t lay claim to being the birthplace of a great politician, or an eminent scientist, or even some famous deviant, serial killer or chef. The closest thing Geraldine has to a celebrity is Jordan Luck: frontman of the band The Exponents. And even then, Mr Luck is actually from Woodbury, five miles west of Geraldine. He did, of course, attend Geraldine High School, my alma mater. He was, in fact, a year ahead of me, and his sister, Tamsin, and I were in the same year. But although The Exponents are an iconic New Zealand band, their fame, unfortunately, hardly extends beyond our shores.

Furthermore, the South Island of New Zealand doesn’t exactly occupy a prime position on the globe. Our island is close to the uttermost end of the Earth. It’s about as far south as you can go on the planet. Go much further and you start to go north again. Go b eyond Bluff, the southernmost town in the British Commonwealth, and the next upright creature you’ll run into is an Adelie penguin. That’s how far south we are.

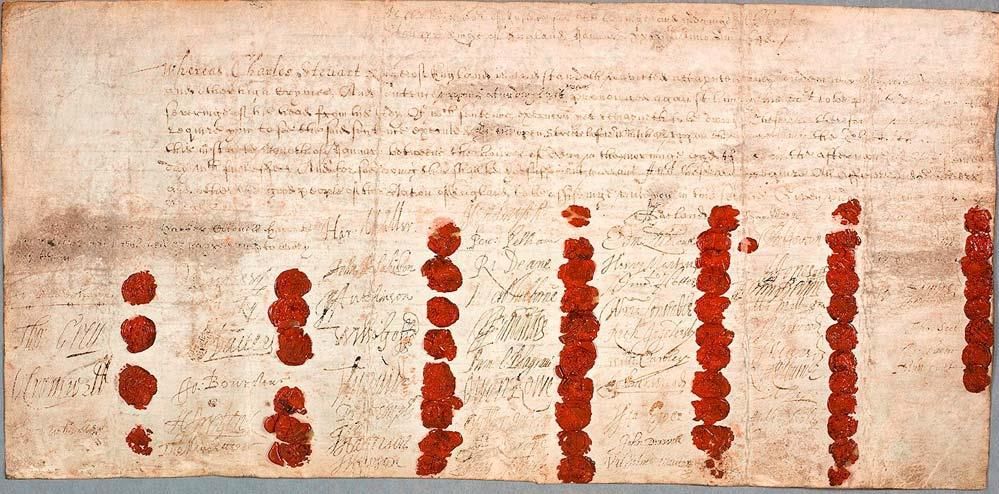

As well as coming from the arse-end of the planet, I also come from a long line of travellers: restless souls who roamed the globe searching for adventure and a better life. Some of them were seekers of political change, such as John Blakiston (1603-1649), whose signature appears on the death warrant of Charles the First, executed by Oliver Cromwell and his henchmen – of which JB was one, the traitorous bastard – during the English Civil War.

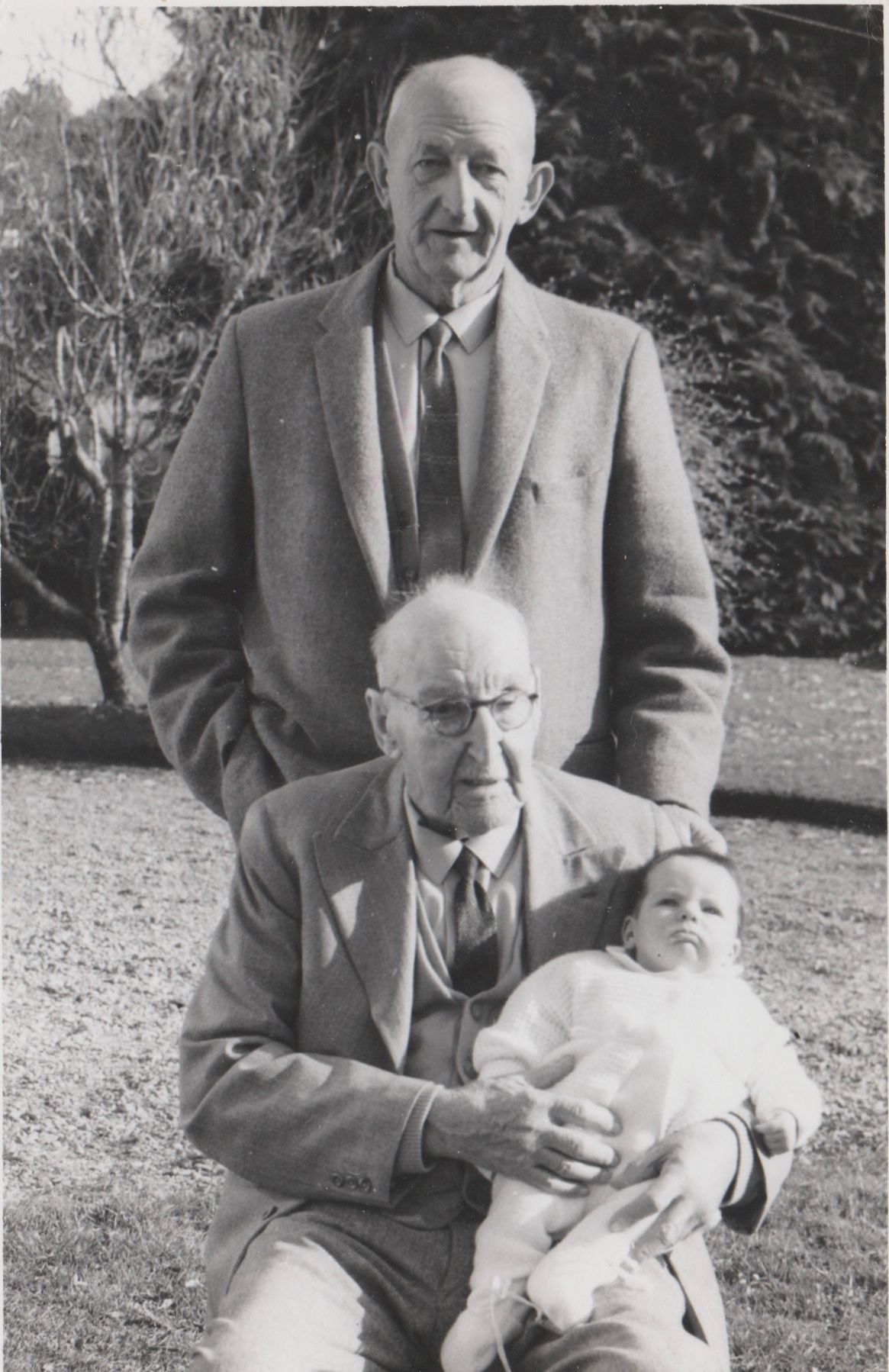

My great-grandfather, Charles Robert Blakiston, came to New Zealand in 1860, having first tried his luck in the Australian goldfields. When he arrived in the settlement of Christchurch (which is today New Zealand’s second largest city) he traded a horse for a plot of land which he subsequently sold to the fledgeling city for a fortune. He ended up a successful lawyer and member of the New Zealand Provincial Government. His son, Arthur John Blakiston, born in 1862, managed a high country sheep station for forty years and lived long enough to be photographed holding me as a five-month-old baby in 1963.

Another of my great-uncles, Thomas Wright Blakiston, was an eminent explorer, soldier and ornithologist. He fought in the Crimean War, was on the Palliser Expedition which mapped the border between Canada and the United States, explored the Yangtze River during the Taiping Rebellion, and lived in Japan’s northern-most island, Hokkaido, for 21 years.

Then there was Lionel Blakiston, Thomas’s cousin. Lionel was a British telegraph engineer who emigrated to Rhodesia in the 1880s and was subsequently killed in the Mashona Uprising. Upon hearing that Mashona tribesmen had taken a group of women and children hostage, he rode to their rescue, bringing them home to friendly territory but getting mortally wounded in the process. A street in Harare, in present-day Zimbabwe, bears his name along with a school, whose coat of arms is that of the Blakiston Family: a cock gules above a bar argent.

In 1760, my great-great-great-great-great-great-grandfather, Matthew Blakiston was elected Lord Mayor of London. He lived for that year, as all Lords Mayor did at the time, in the Mansion House, a grand, collonaded residence opposite the Bank of England. His wife, Emily, is the only woman ever to have given birth in the Mansion House. Lords Mayor were usually older men for whom the post was the final, crowning achievement at the end of long, successful careers. Blakiston, however, in keeping with a family trait of marrying and producing offspring late in life, was still in the process of creating a family when he became Lord Mayor and his son, Matthew, was born at the Mansion House that year.

For his efforts as head of the City of London, Matthew Blakiston was created a Baronet in 1763, exactly 200 years before I was born. He died in 1791 and was buried in the graveyard of St. Martins-in-the-Fields.

The Baronetcy is a hereditary knighthood: a “Sir” rather than a Lord, and not a peer. Although the term “baronet” has medieval origins, the modern Baronetcy was established in 1611 by King James 1 as a method with which to fund his Irish wars. The idea was that any man who could provide the Exchequer with the money necessary to keep thirty soldiers in the field for three years would be granted a Baronetcy. The title would be handed down from father to son, thus ensuring a continual supply of cash to fund whatever war happened to be going on at the time.

Fac bene nec Dubitans

This proved to be a nice little earner for a while; at least, that is, until the sons succeeding to the title began to run out of money. Just because the title of Baronet had been granted to a wealthy great-grandfather didn’t necessarily guarantee the family fortune would still be intact for his great-grandson to invest in dubious overseas campaigns. The Baronetcy, therefore, lapsed in its role as a revenue supply for the army and became simply another hereditary title.

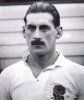

The Baronetcy awarded to Matthew Blakiston was passed down from father to son for seven generations until it hit a dead end. The 7 th Baronet, Arthur Frederick Blakiston, a

decorated First World War hero, member of the first Barbarians rugby team and Master of the Wylie Valley Hunt, died “without issue” (i.e. without children). It seemed that the title would become extinct. But the tireless heralds at the Royal College of Arms, keepers of the arcane language and symbols of the realm, were on the case. They traced the male line to my father, Arthur Norman Hunter Blakiston, who acceded to the title of 8 th Baronet in 1974.

Dad never set any store in airs and graces. A privately-educated, university-trained solicitor he was nevertheless a rough diamond. He called a spade a fucking shovel and to him, a man’s worth was proved by his actions, not by his breeding. The title of Baronet was the absolute antithesis of the egalitarian principles he lived by. But he was a perceptive man and he realized that one day, his eldest son might have a use for the title, so he reluctantly accepted it, and that was that.

He seldom spoke of it. His friends occasionally ribbed him about it. My mother’s friends began calling her Lady Blakiston and our house became known as Sandybrook Hall, after the family seat in Ashbourne, Derbyshire. At school, I was sometimes teased about it. My best friend, Keats, used to call me Sir Bastipol Bock for reasons known only to him. But it was nothing that caused even the remotest bit of hurt and the perpetrators would soon tire of hassling me and find some other unfortunate to pick on.

I was born at 11:20AM on February 19th, 1963. It was a Tuesday. It was the last month of summer in the Southern Hemisphere. According to “The Internet”, I had been conceived on May 29th the previous year!! That same February day, Seal Henry Olusegun Olumide Adeola Samuel was born. He would go on to become the British singer Seal who would write a song called Crazy with includes the lyrics: “in a sky full of people only some want to fly; isn’t that crazy…”

We lived in a big old house at 28 McKenzie Street, Geraldine. The house had originally been a boarding house. It had big rooms, high ceilings and a long hallway, six feet wide and thirty feet long, running down the middle. Myself, my brother Joe (fourteen months younger than me) and our friends would build blanket forts in the hall on wet days and throw marbles at each other. We had our own rooms and there were enough spare rooms for us to have winter and summer rooms: warm rooms in winter and cooler rooms in summer. The red, corrugated iron roof amplified the sound of rain and one of my favourite sounds is still the sound of rain falling on a tin roof.

Our house stood on an acre of land in the centre of Geraldine. There was a hen coop, an orchard, a couple of fields where we kept our pet lambs, and a big oak tree where we built a rambling tree hut. Across the road, the Waihi River chattered in its bed of stones, hemmed on both sides by willows and sycamores. We tickled trout, built dams, rafted the brown floods, and swam in the green pools of the Waihi (it’s pronounced “why-hee”). On the hill beyond the river, Talbot Forest (the Bush, as we called it) was a venue for wargames, hide and seek, and clandestine cigarettes.

Geraldine in the 1970s was a backwater. It serviced the local farmland; old folks retired there. In summer, the sun would melt the tar on the main street and the grass would be burnt brown for months. Winters were harsh, or seemed to be, and I remember biking to school in shorts even in the hardest frosts. There were WW2 veterans in our town: battle-scarred, lame old men with haunted eyes. Women wore floral dresses and men wore hats. It was the same as every small town in the world. It was a colonial town, out on the edge of the British Commonwealth.

I was a cub scout. I hated sports. I ran in the cross country team because it allowed me to get away by myself. I was never a team player. I was a frail, sickly boy. I got bullied a bit at school but nothing serious, nothing scarring. My friend Steve Keats was a runner too and we started climbing hills to keep fit. That was the beginning of my love for the hills and for the wilderness. Our heroes were mountaineers – Chris Bonnington, Sir Edmund Hillary – and our bibles were accounts of epic climbs and disastrous expeditions.

My mother was a church-goer; my father wasn’t. He set store in a man’s self-reliance. He hated pretence and people who considered themselves above others because of birth or money. He was a man’s man. He’d been educated at a prestigious boy’s school and could quote Shakespeare and speak Latin. He swore like a fucking trooper and used to say that he hadn’t learnt a new swear word since he was seven. And, like his son would be, he was a loner.

Mum went to St. Mary’s Anglican church most Sundays. Anglicanism is a very English faith: quiet vicars, ornate churches with stained glass windows, a subdued, reverential communion, no fire-and-brimstone sermons. Both my brother and I were “confirmed” meaning we were able to take communion (that is drink the blood of Christ and eat his body). It all sounds so weird and arcane now. I didn’t believe a word of it. But we went along for mum’s sake. We both did altar boy duty on alternate Sundays once a month. You dressed in black vestments which smelled of body odour, and helped the Vicar out with the communion. I would sit in the carved wooden chair at the side of the altar and pick out rock-climbing routes across the vaulted wooden ceiling. We worked out that if you volunteered for the early 8AM service (which no one wanted to do early on a Sunday) you’d be out of there in forty minutes. The 10:30 service lasted an hour and a half!

My father died in 1977 when I was fourteen. He was seventy-eight years old. Students of arithmetic will notice that he would have been sixty-four when I was born and they are right. He was sixty-five when my brother Joe came along. That same family peculiarity, of having children late in life, that had seen Matthew Blakiston’s wife produce the Mansion House’s only baby, had surfaced again.

It meant that instead of being born in the 1920s, as would have been the case if dad had taken the usual route and started a family in his twenties, I grew up in the 1970s. It meant that instead of being a fan of Bing Crosby or Cole Porter, I was able to become a fan of Pink Floyd, Genesis, My Chemical Romance and John Denver. It meant that instead of having to go off to World War Two and have my brains blown out for King and Country as my Uncle Jim (my mother’s brother) did, I was able to watch the Gulf War on CNN. It meant that I would be able to be a part of the technological revolution created by the internet and social media. And it meant that in the year 1988, instead of being a grandfather of seventy-something years, I was able, as the 9 th Baronet of the City of London, to set off out into the world and put into practice the family motto, Fac bene nec dubitans …Do well and doubt not.